Chapter 13 - Chain of Succession

The Gooding Interlude

By the end of the last century, Tek's thinking finally fell in line with Soros. Meyers had been running the numbers each year through the 90s to see if more value was wrung out of the company by keeping it together or splitting it apart. By the end of that last decade, with Printers growing, and VND and the group cratering, the time had come. Tektronix divested its printing, video and networking divisions. The printing business was sold to Xerox. Tek itself went back to concentration on its test equipment roots.

It sold the video business to a private investor, Terence Gooding of San Diego, California, who reincorporated it under the name Grass Valley Group, Inc. The sale closed on September 24, 1999. Gooding was a private investor based in San Diego. Tektronix kept a 10% equity stake in the new venture, which continued to be based in Nevada City, with an engineering design center inherited from Tektronix in Beaverton, Ore. While Tek had dropped the "Group" from the name a few years prior, Gooding added the moniker back, so the company again was the Grass Valley Group. Besides the traditional switcher and router markets the Group kept the Profile server group up in Oregon.

The investor group led by Gooding, included Thorsteinson, who moved over to the new venture from Tek. Gooding served as chairman and Thorsteinson as CEO of Grass Valley Group. Larry Neitling continued on as the Operations Manager. With an additional Lazard Asset Management Group investment of $34M in capital, Gooding and investment partners promised to fund the new company's working capital and acquisition needs until it reached a level of fiscal maturity appropriate for outside funding. They eventually pumped $100M into the R&D effort.

The new company had annual sales of $200 million in 2000 with 700 employees worldwide. To help build the company it tried focusing not only on television broadcasting, but emerging markets, such as the Internet to electronic projection, as well, with little effect

Thorsteinson had three goals for the new company:

• A narrower focus on its strengths, namely the video server area where GVG's Profile maintained the its number one market share, as well as Grass Valley switchers, routers, and modular products. Over the preceding several years, Tek had tried its hands at PCs and nonlinear editing systems, but found the market to be saturated and unresponsive.

• Reducing costs, GVG consolidated from three manufacturing plants to its Providence Mine operation in Nevada City, reducing costs from $45 million per quarter to $19 million per quarter.

• Competitive pricing, including using commodity microprocessors to reduce manufacturing costs.

While the company was resting on the success of its Profile servers and its well-known switchers, but in a rapidly changing broadcast landscape, it gave them a little breathing room as it was again becoming competitive in its core products. The consolidation back to home turf was to last only for a couple years. The expansion away from the Grass Valley area was soon to begin in earnest.

When Goodman took over the Group, revenues from new products introduced within the previous 12 months represented less than 10% of Tek's VND division revenues, as most of the products selling had been introduced 5 or 6 years ago. "If you don't offer new products every 18 to 24 months, you won't succeed in this business." Thorsteinson said at the time.

As Tek was selling the Group, it was launching a new production switcher, the Kalypso. OB operators loved it, as it had many new innovations for high end production. Launched at IBC in 1999, it took the switcher concept another quantum leap forward, becoming what the Group called the "video production center," putting still stores (and later clip stores) and graphics file conversion right into the switcher, along with multiple effects banks and other creative power.

Thorsteinson and the group were taking additional action. They invested $60 million in research and development in 24 months to develop new products. The plan was to continue spending 13% to 15% of sales on research and development, which would have been $30 to $35 million annually on R&D.

In the router realm the company, in 2000, introduced the 7500 wideband routing system. Early on with HD reclockers for the signal did not work very well. The answer early on was to just build routers with as wide a bandwidth as possible. The 7500 could work with signals ranging from 10 KB/s to 1.485 GB/s HD bit rate.

They also tried marketing the Voodoo Media Recorder. With 32 heads, this SMPTE D6 gigabit recorder could record either uncompressed HD or data streams up to 128 MB/s. While impressive, it was very expensive due to the speeds, and the space that uncompressed media data required. It was a bit a head of its time technology wise.

Avstar was launched, which was a joint newsroom automation project between Avid and GVG. The Group contributed their Newstar product to the effort, and while at the time Gooding said that it "remains an important part of the company's business," he also said that GVG will rely less on joint ventures moving forward. "It takes so much work to do a joint venture." He decided to sell off their Newstar product line to Avid 2001.

In 2001 the GXF container format (informally, sometimes called a wrapper) or metafile was introduced. This was a file format that allows multiple data streams to be embedded into a single file, usually along with metadata for identifying and further detailing those streams. Grass Valley had started development on it for their Profile servers. SMPTE formalized the standard as SMPTE360M as a broadcast industry audio/video file interchange format based on Profile video servers.

The company continued Profile development by introducing the Profile Media Area Network, which provided shared storage for up to 48 channels. This allowed truly enterprise wide storage and delivery.

Under Gooding and Thorsteinson the Zodiak digital production switcher was introduced in 2001 for mid range applications. It was an effort to replicate its analog market share in live digital production, which offered many of the high end features of the company's flagship Kalypso Digital Production System but carried a smaller $125,000 price tag verses Kalypso's starting price of $185,000. Affordability was a major factor that had made the analog GVG model 200 and 250 the veritable workhorses of the industry. The company was hoping to replicate that in the digital realm. But again, these were SD switchers, and not HD.

Thomson came a calling in 2002. It was looking to bulk up it's offerings in the media arena. This wouldn't be the only time that Grass Valley was acquired with that object in mind. Thomson payed $172 million. The changes that Tek had contemplated for the Group were mild for what was soon to happen. This was the second time that Thorsteinson was involved with selling the same company. It wouldn't be the last.

Thomson's Turn

In April 2002, the French electronics giant Thomson Multimedia, today known as Technicolor SA, became the third owner of the Grass Valley Group. Combined the two companies were $500 million a year concern.

Under Thomson, Tim Thorsteinson, the former president and CEO of Grass Valley Group, became the vice president of the combined switcher, server, digital news production, router, master control, facility control and modular product lines. Thorsteinson, who has made his reputation on his commitment to R&D, at the time said the new R&D team would be split between Europe and the U.S. He said working from two continents does have its advantages. "There's always a feature set that our guys didn't quite get for the production switchers, or we did big routers when Europe was going to compact routers," he said. "Having a design presence in a geography and having people visit customers there is a tremendous advantage."

Thomson had already enlarged its broadcast activities earlier that year when it acquired a majority interest in the Philips Professional Broadcast Group. Thomson thought the transaction would reinforce Thomson's access to the professional U.S. customer base. At the time of the sale Thorsteinson said, "Our goal is to take the things we've been successful at and carry them forward, and the upside of this whole acquisition is that we're now part of a company that is focused on the total media space and we're part of a large company that has a capital base. The challenge of what we've been doing the last couple of years is that we've been very thinly capitalized. So keeping the engineering spending where we kept it, 15-20% per year when we're in an industry recession and we're capitalized by basically one person was difficult." None–the–less Thorsteinson was soon gone, but his influence on the company was not done.

Thomson had already enlarged its broadcast activities earlier that year when it acquired a majority interest in the Philips Professional Broadcast Group. Thomson thought the transaction would reinforce Thomson's access to the professional U.S. customer base. At the time of the sale Thorsteinson said, "Our goal is to take the things we've been successful at and carry them forward, and the upside of this whole acquisition is that we're now part of a company that is focused on the total media space and we're part of a large company that has a capital base. The challenge of what we've been doing the last couple of years is that we've been very thinly capitalized. So keeping the engineering spending where we kept it, 15-20% per year when we're in an industry recession and we're capitalized by basically one person was difficult." None–the–less Thorsteinson was soon gone, but his influence on the company was not done.

After coming under the ownership of Thomson, Grass Valley Group was forced to merge its product line with the existing professional and broadcast products of its new parent company, with mixed results. This is when the vast majority of the corporate DNA, today infused behind the Grass Valley moniker, occurred as we will see. While it was known as Thomson–Grass Valley then, a lot of the assets, and baggage that Thomson brought stayed under the Grass Valley name when the company was sold later for the 4th time.

Thomson's Ancestry

The lineage of Thomson is the convergence of five lines of companies. We will look at them now.

Thomson

Thomson was named after the electrical engineer Elihu Thomson, who was born in Manchester, England, on March 26, 1853. Thomson moved to Philadelphia, USA, at the age of 5, with his family. Thomson formed the Thomson–Houston Electric Company in 1879 with Edwin Houston. The company merged with the Edison General Electric Company to become the General Electric Company in 1892. In 1893, the Compagnie Franċaise Thomson-Houston (CFTH) was formed in Paris, a sister company to GE in the United States. It was from this company that the modern Thomson Group would evolve.

Thomson was early to digital, producing their first Digital Noise Reducer in 1977. In 1986 Thomson demonstrated Le Studio Numerique, the world's 1st full component digital studio. Later the system was installed at SFP, Paris. In 1992 Thomson introduced a Motion Compensated Standards Converter.

Hi powered television transmitter

Thomson-CSF acquired U.S. transmitter vendor Comark Communications, along with Comwave and formed Thomcast Communications to strengthen their worldwide presence in television transmitters. In the late 80s Comark was known for pioneering very high power television transmitters, using an off spring of the Klystron vacuum tubes which were much more efficient than their ancestors. Comark was selected to supply the transmitter system for the Model HDTV station Project.

In the early 90s Thomcast added Asea Brown Boveri (ABB), a Swiss transmitter and antenna company to its transmitter portfolio. In 2000 Thomson–CSF divested its military and transmission product lines creating Thales. Thomcast becomes Thales Broadcast and Multimedia.

(Confusing!) In 2003 Thales pioneered the development of Digital Modulator Pre–Correction for ATSC 8-VSB.

In June 1998 in a deal brokered by the French government, parts of Aerospatiale, Alcatel, and Dassault Industries came under the Thomson umbrella. The French State's interest in Thomson was reduced from 58% to 40%, and Alcatel and Dassault Industries became shareholders.

Bosch

Bosch GmbH was founded in 1886 and made magneto ignition devices for gas turbines and later automobiles. It branched out into other auto parts and became an armaments supplier for Nazi Germany.

Early Fernseh television camera

In 1939 Bosch took control of Fernseh, which started in 1929 as a television technology research firm on behalf of others. Fernseh is believed to have created the first remote television truck in 1932. Soon the combined company was known as Bosch Fernseh. In 1967 the combined company introduced its first color TV.

In 1975 it introduced what was known as a B-format VTR

By the 80s Bosch, besides still in the automotive parts business, the company had a full line of broadcast television equipment.

Bell & Howell

B&H 8mm film projector

B&H 8mm film camera

Bell & Howell was founded in 1907 by two projectionists to manufacture film cameras, lenses, and motion picture machinery. In 1954 KUTV signed on in Salt Lake City. In 1962 a joint venture between the station and the Salt Lake City Tribune, Telemation was founded. It developed and sold a line of industrial quality, not quite broadcast quality, television equipment. In 1971 they introduced their first color camera and followed with a color film chain in 1973. In 1974 they offered their first television router.

Bell & Howell purchased the company in 1977. In 1979 they entered into a joint venture with the Bosch Fernseh Division. In 1982 Bosch fully acquired the venture renaming the company Robert Bosch Corporation Fernseh Division.

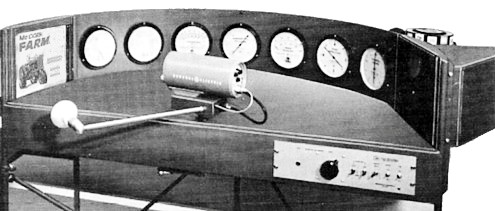

60s TeleMation 495 "Weather Channel" "automation system."

Connected to a wind gage and other instruments on the cable company's roof. The "weatherscan" camera slowly panned back and forth across the analog clock, dials, and ads.

Philips

The Philips Company was founded in 1891, and its first products were lamps. In the 1920s, the company started to manufacture other products, such as vacuum tubes. In 1939, they introduced their electric razor, the Philipshave which was marketed in the US using the Norelco brand name. What Philip became very well known for in the broadcast industry was their cameras. Their first big hit in the U.S. television market was their ground breaking PC-60 color camera which was introduced in 1964.

PC stood for Plumbicon Color. The "plumbicon" imaging tube was a much more sensitive, smaller, with higher resolution than what had come before. 60 stood for the year the Plumbicon was invented. In the U.S., the camera was also sold under the Norelco brand. Yes, the same folks who had been selling electric razors. An early pioneer in television, Philco, in 1940 claimed that Philips name was too similar to theirs, and got the FTC to block any products from having the Philips name on it in the U.S. So they set up a subsidiary called North American Electronics, or Norelco for short. So everywhere else except the U.S., when the Norelco PC-60 launched, it was known as the LDK-1. LDK is the Dutch abbreviation of the lead oxide tube, which is what comprised that image target in the plumbicon tube. Finally, in 1981 Philips acquired GTE, who had acquired Philco from Ford Motor. Ford had bought Philco in 1961. Philips could now brand itself Philips everywhere.

PC-70, which soon followed the PC-60. The camera that made ABC and CBS get serious about color

Up until then both networks were avoiding broadcasting much in color. ABC because it didn't have the money to spend on color equipment. Color cameras were going in the $100K range, in 1960s dollars. Plus all the ancillary equipment was also more expensive than black and white equipment.

CBS's reason was more strategic. While companies such as Marconi were offering color equipment, the dominant player by far was RCA. They had invented all electronic color and sold the vast majority of color gear at the time. RCA also owned NBC, which CBS deemed their major competitor. CBS was in no mood to indirectly help their competitor. While by 1960 NBC was for all intents a full color network, CBS had less than a dozen color cameras across the entire network. The rational that CBS used at the time was that they would provide color programs when the advertisers would pay for it. NBC had the luxury and rationale, a generation earlier than we saw with Sony, of producing shows in color to fuel color set sales. At that time RCA was the dominant home receiver manufacturer, along with being the dominant color production equipment supplier. Much like Sony was in the 80s and 90s.

CBS was so against having to buy color equipment that they fought RCA's efforts to standardize color on their system. They even designed a color system that used a spinning "color wheel" or disk as a competitor to RCA's all-electronic approach. Besides the mechanical attributes, it was a much simpler system electronically. The state of the art in electronics in the early 50s made the CBS approach much more stable. But while RCA's system would not obsolete existing black & white sets, CBS's would.

Much to CBS's dismay the FCC actually adopted the CBS system for a while. That was not CBS's end game. Their real motive was to stymie the RCA system. CBS's rationale was that they had just a few years earlier, during the late 40s, spent an awful lot on RCA black & white equipment, they did not relish having to do that all again on RCA color equipment. For a while they scambled to go into the color home receiver business. They were given an out by the start of the Korean War. Ostensibly by request of the National Production Authority "to conserve material for defense" for the duration of the Korean War. CBS announced, almost too quickly some thought, that it agreed and would also drop color broadcasts; color receivers were recalled and destroyed. Only a couple hundred were ever produced. Strangely, monochrome receiver production was not affected. RCA eventually perfected their system enough to release it for sale. Even then, the industry group that standardized RCA's system, the National Television Systems Committee, or NTSC, some claimed the initials actually stood for "Never Twice the Same Color!"

Philips had over 1000 of their state of the art cameras out in the field by 1968.

The PCP90 minicam was introduced in 1969, and the PC100, the first triax cable camera a year later. The first introduced a truly broadcast quality camera head that could be strapped to a person's back. The second one heralded the use of modified coax to connect the camera with the rest of its electronics, instead of fat multi-conductor cables.

In 1967 Philips acquired control of Pye Ltd, which was an electronics company founded in 1896 in Cambridge, England, as a manufacturer of scientific instruments. The company eventually offered a line of TV sets and television transmitters.

In 1975 their second generation of the LDK series of cameras was introduced. In 1979 the FDL 60 Telecine was introduced. It was the 1st telecine to use CCD sensors. Philip's LDK6, their first totally automatic camera was introduced at NAB in Dallas 1982.

Over the years Philips developed a number of firsts found today in high end cameras. These include "crispening" circuitry that sharpened the transitions in a video signal resulting in the appearance of a sharper picture. They also pioneered the selective application of such circuitry, by controlling the amount of sharpening that was added to flesh tones to hide wrinkles, which they developed in 1993. A big development came in 2000 when they created the HD-DPM imager technology for CCDs allowing for the first time a sensor to be set up for scanning in one of several native HD formats, a development we covered earlier.

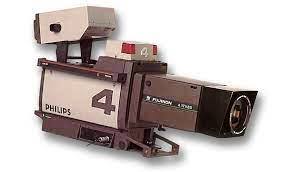

Current model of studio camera when Grass Valley and Philips were first involved with each other. Philips also competed with Grass Valley in switchers and routers.

BTS & Philips Broadcast

In 1986 BTS, Inc. was formed as a joint venture between Bosch and Philips. The Robert Bosch Video Division, comprised of the Salt Lake manufacturing facility, acquired from Telemation, and a sister manufacturer in Germany were joined with a Philips television camera manufacturing facility in the Netherlands, to become Broadcast Television Systems or BTS, Inc. In 1992 BTS became a wholly owned member of the Philips family, retaining the BTS name. In 1992 parts of the Albertville Winter Olympics were covered in HDTV for the 1st time with HDTV OB vans and equipment from BTS.

In 1986 BTS, Inc. was formed as a joint venture between Bosch and Philips. The Robert Bosch Video Division, comprised of the Salt Lake manufacturing facility, acquired from Telemation, and a sister manufacturer in Germany were joined with a Philips television camera manufacturing facility in the Netherlands, to become Broadcast Television Systems or BTS, Inc. In 1992 BTS became a wholly owned member of the Philips family, retaining the BTS name. In 1992 parts of the Albertville Winter Olympics were covered in HDTV for the 1st time with HDTV OB vans and equipment from BTS.

BTS equipped OB van

In 1995 Philip re–branded BTS as Philips Broadcast. Philips Broadcast stayed a brand until 2001 when it was acquired by Thomson multimedia SA, merging the company with Thomson's own broadcast division into Thomson Broadcast and Media Solutions (TBMS) business group. The groups product lines among many other things included cameras, routers, switchers, and even VTRs.

Technicolor

In 2000, Thomson Multimedia purchased Technicolor for $2.1 billion from Carlton Television (owned by Carlton Communications) in the UK and began a move into the broadcast management, facilities and services market with the purchase of Corinthian Television, becoming Thomson Multimedia.

Bulking Up

Early on in his career the author had a boss who often said

"If RCA doesn't make it, we don't need it!"

A common line uttered through the 60s as RCA sold the entire length of the television equipment food chain. At it's height RCA was like IBM and the Seven Dwarfs in the television realm. Interestingly RCA was one of the seven dwarfs in the computing realm at the time. During it's rein in television many wanted options other than RCA. The camera on the left sold briskly when it was introduced in the 1960s because it did not have RCA's logo on the side of it (yes it is the same model that had the ABC logo on it a bit earlier). CBS hated RCA so much (as they owned their largest rival - NBC), that they would pry RCA logos off the RCA equipment they were forced to buy. As mentioned a bit ago CBS originally fought the implementation of RCA' all electronic color television, so as not to have to buy more equipment from them.

Interestingly in 1988, 2 years after General Electric Company bought RCA, they sold their consumer electronics division, to Thomson-CSF, in exchange for some of Thomson's medical businesses. At one time it held the RCA trademark rights.

With the addition of Grass Valley in 2002, this was to be RCA Broadcast for the new century, to offer products from cameras to transmit antennas under one umbrella. Only RCA was able to accomplish that until GE bought them in 86 and dismantled them. Thomson had managed to roll up a dozen companies into its consortium. But the conglomerate was not done.

Thomson then purchased the Moving Picture Company from ITV and the Internet startup Singingfish, but then sold it to AOL in late 2004.

In 2004 Parkervision, Jacksonville, Florida company was bought for $14 million, adding automated news production systems and robotic camera lines. This added 143 employees to the company which then had over 73,000 worldwide employees. What Parkervision offered to it's clientele was the ability to run a production control room, say during a newscast, with one employee instead of the four or five normal required in a mid–sized market.

In 2004, Thomson set up a joint venture with China's TCL (TTE), giving to TCL all manufacturing of RCA and Thomson television and DVD products. This made TCL the global leader in TV manufacturing, while Thomson still controlled the brands and licensed them to TTE. At the time, TCL was hailed as the first Chinese company to compete on the international stage with large international corporations. Thomson initially retained all marketing of TTE's products, but transferred that to TTE a year later. Thomson sold the Indian company, Videocon Group, the display manufacturing business for about $250 million. In early 2010, Thomson sold the television brand RCA to ON Corporation.

Next on the menu was Canopus Co., a manufacturer of video editing cards and video editing software, which was acquired in 2005 for $107 million. The company's video cards had competed with the likes of Matrox and Pinnacle Systems. In 2003 Canopus introduced their EDIUS nonlinear editing software.

Thales television transmitter at WMHT in Schenectady, New York, a PBS station in 2003

In its quest to cast as wide a net as possible in product offerings, at the end of 2005 it also bought back Thales Broadcast for $155.6 million, which it had sold off earlier. This brought a line of radio and TV transmitters, antennas, and a line of MPEG test equipment into the fold. It also added Nextstream, with compression product lines for telco, cable, and satellite segments.

Together, these acquisitions completed Thomson's two year plan to enhance its claim as "a worldwide leader in end to end systems for distributing multimedia content over broadcast, cable, satellite, and the emerging market for sending video over Internet Protocol, also known as IPTV."

The problem was there were some product overlap. Both Grass Valley and Philips made production switchers and routers. In fact Grass Valley's Trinix router was introduced almost at the same time that Philip was developing their venerable line of Venus routers. Also, both Philips and Thomson offered high end cameras.

Marc Valentin became the Grass Valley's Division president, replacing Thorsteinson.

Valentin started with Thomson in 1993 as a corporate planner. In 97 he became Chief of Staff which meant the managing and organizing of Thomson CEO's presentations, management meetings and management schedule, then moved on to be Vice–President, Digital set–top–boxes Europe. In 2002 he became head of the entire company, which interestingly was now called Grass Valley. He was tasked with integrating the former Philips Broadcast business and Grass Valley Group into the rest of the company.

When Thomson had taken over the company it became known as Grass Valley, a Thomson brand. By 2005 Thomson realized that the Grass Valley brand was stronger than Thomson's, at least in the professional television realm in the states. So the Grass Valley brand was applied to all activities of the division, including the website; www.thomsongrassvalley.com became www.grassvalley.com. All traffic to the former web site was now automatically directed to the new site. While the brand name was as strong as ever, with much expanded product lines, the namesake of the company was losing its grip on the company.

In 2003 the first joint switcher project between Philips and GV design teams produced the KayakDD Digital production switcher for low to mid–range markets, with many features of the Zodiak.

In 2005 Premier Retail Networks (PRN) was acquired by Thomson for $285 million. The company did digital sign–age for companies such as WalMart. Also in 2005, what many said would never happen, that is up until the Thomson acquisition, a Grass Valley product with a lens hung on the front of it. A Thomson-Grass Valley camera was introduced at IBC.

In 2006 the Grass Valley Division teamed with Polatis which was a provider of optical switching products for the communications, video, defense and instrumentation industries in an attempt to re–enter the fiber market.

In 2007 the "French conglomerate" as it was often referred to, decided to replace Valentin with Jacques Dunoguè, and realign the structure of the business. Dunoguè was the Senior Executive Vice President in charge of Thomson's Systems Division. At the same time steps to strengthen and reinforce video networking and systems integration synergies with Thomson's other related businesses were also taken. Grass Valley, with Philips firmly under the GV brand, were organized into three business units: Broadcast & Professional Solutions, Integration & Transmission Solutions, and Video Network Solutions. At that time Jeff Rosica, who had been managing Grass Valley's North American sales and marketing efforts, continued on in that role and also lead the Broadcast & Professional Solutions business unit, reporting directly to Dunoguè.

The implosion

In 2008 the housing bubble broke, culminating into a "perfect storm" that became known as the Great Recession. Up until Covid19, it was considered by many economists to have been the most serious financial crisis since the Great Depression. It was a worldwide recession.

It was precipitated by predatory lending targeting low–income home buyers, and a vast web of derivatives linked to Mortgage–backed securities, tied to American real estate, which collapsed in value. The increase in cash out refinancing, as home values rose, fueled an increase in consumption that could no longer be sustained when home prices went into decline. The U.S. home mortgage debt relative to GDP increased from an average of 46% during the 1990s to 73% during 2008.

U.S. mortgage debt was at $10.5 trillion. In March 2008, the Federal Reserve allowed Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to buy $200 billion in subprime mortgages from banks. Officials thought this would contain the possible crisis. But the U.S. dollar weakened, and commodity prices soared.

Global financial institutions started failing. Also Bear Stearns, with $46 billion of mortgage assets that had not been written down and $10 trillion in total assets, faced bankruptcy. The Federal reserve held its first emergency meeting in 30 years, the Federal Reserve agreed to guarantee Bear Sterns bad loans to facilitate its acquisition by JPMorgan Chase in a fire sale. Stearns stock had fallen from $178/share a year earlier to $60/share. Chase bought it at $10/share.

In late June 2008 the U.S. stock market had fallen 20% from its highs, and commodity-related stocks soared as oil traded above $140/barrel for the first time and steel prices rose above $1,000 per ton.

Financial institutions worldwide continued to suffer severe damage. This reached a climax with the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers on September 15, 2008. The Federal Reserve declined to guarantee its loans as it did for Bear Stearns. The Bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers, the fourth-largest investment bank in the United States, led the exodus of most of its clients, drastic losses in its stock, and devaluation of assets by credit rating agencies, largely sparked by a loss of confidence, Lehman's involvement in the sub–prime mortgage crisis, and its exposure to less liquid assets. Lehman's bankruptcy filing was the largest in US history.

Barclay acquired what was left of Lehman's North America operations for $1.35 billion. What it basically got was its $960-million headquarters, a 38-story office building in Midtown Manhattan, and the responsibility for 9,000 former employees severance pay.

To avoid bankruptcy, Merrill Lynch was acquired by Bank of America for $50 billion in a transaction facilitated by the U.S. government.

In what continued to be a bad September, the Federal Reserve took over American International Group with $180 billion in debt and equity funding, and technically assumed control, because many believed its failure would endanger the financial integrity of other major firms that were its trading partners. These were Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, Bank of America, and Merrill Lynch, as well as dozens of European banks.

Next, the equivalent of a bank run on money market funds, investors withdrew $144 billion from U.S. money market funds, which frequently invest in commercial paper issued by corporations to fund their operations and payrolls, causing the short–term lending market to freeze. The withdrawal compared to $7.1 billion in withdrawals the week prior. This interrupted the ability of corporations to rollover their short–term debt. The U.S. government extended insurance for money market accounts analogous to bank deposit insurance via a temporary guarantee and with Federal Reserve programs to purchase commercial paper. By the end of the year the DJIA had dropped another 20%.

The banking crisis spread. Iceland saw all three of its major banks fail. Relative to the size of its economy, it was the largest economic collapse suffered by any country in history. It was also followed by the European debt crisis, which began with a deficit in Greece in late 2009. The ongoing crisis saw $2 trillion erased from the global economy.

The credit crunch wreaked havoc with the paid advertising model for "Free" TV. Station Groups like Sinclair developed consolidation strategies based on centralized operations. The number of separate station owners was decreasing, and thus the equipment they needed was also decreasing. While the station groups total budget for broadcast equipment might have been increasing, the per station spending was declining because of consolidation of ownership groups.

Recent FCC decisions also accelerated this trend, such as ending the Main Studio Rule in 2017. The main studio rule had been in place for nearly 80 years and required AM, FM, and TV stations to have a main studio located in or near the community it was licensed to. At the time, the rule was meant to facilitate input from community members and the station's participation in community activities.

The FCC, in its official announcement, said that it recognized that the public can now access information via broadcaster's online public file and that stations and community members can interact directly through alternative means such as email, social media and the telephone, making the main studio rule "outdated and unnecessarily burdensome." This meant that these ownership groups could consolidate their operations even more, reducing overall spending.

Technology is a great equalizer. It simultaneously erodes and creates wealth. The effect of technology on the Broadcaster has recently been to greatly reduce, if not remove, the power of the broadcaster to control the format in the home. Now the consumer consumes television on a device and format, and at the time of their choosing.

Thomson had revenues of $6.4 billion for the fourth quarter of 2008, a decrease of 12.7 percent compared to the previous year at then current exchange rates, and 7.7 on a constant currency basis. The crises resulted in Thomson defaulting on its financial covenants. Some of the company's private placements required that debt didn't exceed net worth. At the end of 2008 it had a market cap in France of around $460 million. Debt was nearly $2.8 billion. It had a little over $1 billion in cash at the end of the year; money it drew down from the balance remaining on its syndicated credit facility. By the end of April 2009, this covenant was going to be breached.

This triggered some creditors to demand early repayment. Thomson was forced by its creditors to divest its Grass Valley, and PRN digital signage business and other manufacturing entities. On January 29, 2009, Thomson announced the sales of the two divisions. Its stated reason was to focus on services business and improve its financial position. Together, Grass and PRN generated $1.3 billion in sales in 2008, about 20 percent of Thomson's revenues.

At the time the publication TV Technology observed: "Nothing against the French, but that ownership always seemed rocky. From my discussions with many Grass Valley personnel, the relationship between American and Technicolor's (Thomson's) French management was often strained. I more fully recognized one key symbol of the French style of management when GV press releases began listing the value of equipment sales in euros. I asked the Americans why a sale of equipment made in Grass Valley, CA, to a broadcast network in New York would be valued in euros. The paraphrased answer was, 'Because that's what they (the French) want.'"

On January 27, 2010, Thomson changed its name to Technicolor SA, re-branding the entire company after its US film technology subsidiary. Thomson's US subsidiary became Technicolor USA, Inc. Grass Valley went in July 2010 to the Francisco Partners and PRN that December. It also sold off it's transmission business. Thomson had sold the Grass Valley digital film transfer gear business, inherited from Technicolor to private equity investors in October of the year before.

An iconic name in the cinematographic industry, Technicolor was associated with the color process used widely in many celebrated films over three decades including "The Wizard of Oz," "Singin' in the Rain" and "Fantasia." For years, the company had been quietly transforming itself from a film–focused lab to a company providing all manner of digital services, including cinematographic digital processing and visual effects.

An iconic name in the cinematographic industry, Technicolor was associated with the color process used widely in many celebrated films over three decades including "The Wizard of Oz," "Singin' in the Rain" and "Fantasia." For years, the company had been quietly transforming itself from a film–focused lab to a company providing all manner of digital services, including cinematographic digital processing and visual effects.

One of several cameras used to film the Oz scenes. Invented in 1932, the Technicolor camera recorded on three separate negatives, red, blue and green, which were then combined to develop a full-color positive print. The box encasing the camera, a "blimp," muffled the machine's sound during filming.

Like it did with Grass Valley, Thomson originally wanted to stress its own brand over Technicolor's, Thomson Technicolor, which diluted the value and meaning of the Technicolor name. The re–branding of the parent company and the refocusing of Technicolor on its heritage and not Thomson's represented a bold move on where the company thought its future lie. Also, getting rid of a too cumbersome past was certainly a consideration. Chief marketing officer Ah-mad Ouri said at the time "We chose the Technicolor name because it's most relevant to content creators and distributors." In a sign that the center of the company was shifting to Hollywood, Quri was based there. The company's new headquarters was at Sunset-Gower Studios

Technicolor's historic core competency has been in color science, be it it's original giant three-strip film cameras and film processing, is today extended into the video digital realm, as film is no more. What once ended up on film is now a digital bitstream, a "number sequence" to digital signal processing purists.

Next! - Francisco Partners

On January 1, 2011, Grass Valley, with all the additional products accumulated by Thomson, resumed operating as an independent company with offices in San Francisco, California. The sale to Francisco Partners, a San Francisco-based venture capital company, was another fire sale of the company. Essentially Thomson said you take Grass Valley and carry the debt and we will give you an additional $150 million.

Francisco Partners invested in technology and technology-enabled businesses. They looked upon themselves as "turn-around-artists," willing to invest to reposition, re-capitalize and rejuvenate companies, which GV severely needed. At the time it had $5 billion in capital and claimed to have the expertise to pursue enterprise investments ranging from $25 million to $2 billion. The deal was put together by David Golob and Brian Decker.

David Golob

Brian Decker

Golob joined Francisco Partners as a Partner in 2001 and he focused primarily on investments in the software and services sectors. Prior to joining the firm he worked for three other venture firms focusing on technology and software. Early in his career, he was a management consultant with McKinsey & Company and a Product Manager with Newport Systems Solutions, Inc. which was acquired by Cisco. Golem said the Grass Valley deal was just too good to pass up. Essentially they bought the company with no money except taking over the debt.

Decker was a Deal Partner with Francisco Partners, Before Francisco he was a Business Analyst with McKinsey & Company where he focused on the semiconductor, telecommunications, and hardware sectors. Earlier he had product and strategic marketing roles in a couple high tech companies. He represented Francisco Partners on the GV board.

Alain Andreoli

They brought in a Silicon Valley guy. Alain Andreoli joined Grass Valley as CEO from Francisco Partners, where he was an Operating Partner. Just prior, he was President of Sun Microsystems Europe which represented 40% of Sun's business, until Sun's acquisition by Oracle in 2011. He then joined Francisco Partners. Andreoli said the new management was committed to bringing Grass Valley back to its glory days. To many the brand was not as pure as it once was. Many could look at equipment throughout their facility and see the various incarnations of GV and Thomson, maybe even an old Tek/GV logo, on plenty of routers and servers and cameras, some going way back to the old GVG logo with the two mountain peaks. Andreoli said Franciscan Partners was prepared to invest millions over the long term to bring the luster back.

The first thing the company had to do was regenerate standalone departments for finance, legal, HR and so on. Andreoli also indicated that he knew the company needed to rebuild the service arm of the company. To try and do that he turned to another computer person, and hired a new head of service from HP.

Andreoli was aghast at all the custom hardware Grass Valley built. He stated that moving forward the company would do everything with off-the-shelf (OTS) computers. Deja vu, 14 years hence! Maybe Fjeldstad was just to soon? To that end he started an initiative called Galaxy. He cited the parallels between IT, and broadcast technology. He noted how storage had evolved from islands of directly attached storage, through SANs and NAS to unified central storage, either locally, or in "the cloud." He directed the company to concentrate on media "lifecycle management," which ended up as software called Stratus. That part of the project lives on today, having evolved into a video production and content management toolset that organizes workflows.

Graphic depicting Stratus GUIs

Andreoli's view was radically computer centric. While the industry was definitely heading into that camp, it was still not yet quite ready for "prime time," as the processing horsepower, and Internet bandwidth was still not quite there. He stated that the network had become the computer, with on demand utilities like Amazon and Rackspace. One of Amazon's major business units provide servers in the cloud. Rackspace is another. He said that "Our space needs a few specialized but scaled "IBM-Like" leaders who can unify the contents lifecycle management and reduce costs."

Andreoli would contrast the situation that generally existed then, where broadcast technologists preferred to buy proprietary best of breed products. Andreoli often used an analogy. Where hunter-gathers would wonder the wild-wide open spaces to farmers. He described the broadcast industry as the hunter-gathers. He defined the farm as a seamless content management factory, ultimately a utility. He said, "it must change into a farm." To build the farm, he advocated a smaller group of vendors with inter-operating solutions, much like the IT industry had become early in the new century.

This is much like the observation George Hoover, former CTO of NEP Inc., NEP is the largest vendor of production services in the world, had made concerning the remote production industry earlier. Early on he said vendors of such services had been cowboys. They needed to become ranchers to survive.

The world was moving towards wired and wireless connectivity through the Internet. The argument was that broadcasters had to do the same. Specialized hardware would greatly diminish, and that vendors would need to move to sell solutions and services. Moving to file-based operations would allow broadcasters to switch to IT technology, and that closed "best-of-breed" systems would give way to open architectures. He was exactly right as we will see in chapter 18, just wrong about the time frame.

He foresaw one other revolutionary development. The rise of variable operational costs that would replace a lot of capital spending. Renting elements or capability to produce a show from services in the cloud. What use to reside in a facilities equipment or "rack" room would be somewhere else and be much more software than hardware based. While control panels and other operator surfaces might be local, the processing would not.

At that time to move in that direction, GV started development on a localized version of that concept. The K-Frame would allow any of the "K" control panels, such as Kayenne, Kayak, Karrera, Korona, etc. to control central processing in the K-Frame, which they dubbed a video production engine. Switchers, at the time, touted as the backbone of the company, were losing money and market share. While an ambitious project, it took almost three years to go from concept to shipping reality.

The company needed new products. Their routers were getting long in the tooth. The Beaverton server division was producing the Dyno replay system, and while operators liked it, GV was not making a compelling business case for it. LDX cameras, out of the Netherlands, were a bright spot. Another locally engineered product, the GV Director, comprised a switcher, video server, graphics generator, and multiviewer display, with a smart control surface and touchscreen panel, assignable buttons, and a T-bar, provided a simple, powerful, and creative workspace for live monitoring and switching.

At a time when it had embarked on a bold new intuitive with the K-Frame, the company needed to refresh the offerings in another core product, routers, the company was laying off engineers. Bob Weaver, in a blog at the time quipped, "The firings will continue until we ship this product!"

Another product that was getting tired was the Ignite newsroom automation system. At one point GV was going to retire it. But after it won an Emmy they decided to keep it. They released a new software version to update it, but customers never seemed to be impressed with the improvements. It was not competing well with newer competition, and it did not scale down well for smaller markets.

Grass Valley Director

Another big evolutionary development was trickle down technology. A Sony engineer once observed that up until the late 90s, technology from their high end broadcast gear, would eventually find its way into consumer gear. Now it was the opposite. Technology had gathered enough critical mass that new developments would rapidly become economical enough that they would go straight into consumer gadgets. Recently, half-jokingly, it's been suggested that Sony Broadcast high end hardware might be reduced to residing in a Playstation. The Playstation uses a multi-core multiprocessor called the Cell. It combines a general-purpose PowerPC core of modest performance with streamlined coprocessing elements which greatly accelerate multimedia and vector processing applications, as well as many other forms of dedicated computation. Its an early microprocessor that relies on dedicated circuitry video and audio processing and not the microprocessor itself. It was developed by Sony, Toshiba, and IBM.

Another big evolutionary development was trickle down technology. A Sony engineer once observed that up until the late 90s, technology from their high end broadcast gear, would eventually find its way into consumer gear. Now it was the opposite. Technology had gathered enough critical mass that new developments would rapidly become economical enough that they would go straight into consumer gadgets. Recently, half-jokingly, it's been suggested that Sony Broadcast high end hardware might be reduced to residing in a Playstation. The Playstation uses a multi-core multiprocessor called the Cell. It combines a general-purpose PowerPC core of modest performance with streamlined coprocessing elements which greatly accelerate multimedia and vector processing applications, as well as many other forms of dedicated computation. Its an early microprocessor that relies on dedicated circuitry video and audio processing and not the microprocessor itself. It was developed by Sony, Toshiba, and IBM.

This, even back during Andreoli's reign, was happening. A common example even then, were image capturing devices, cameras, and cellphones. Today a person with their iPhone could capture some video at the same time a very high end television camera was doing the same, The cost difference between them could be three orders of magnitude, $100K verses under $1K, and the quality difference would not be objectionable. The earlier broadcast technologist who would search out "best-of-breed" solutions, now could be competing with the concept of "good enough". We have mentioned before that much earlier television technology was much less robust, and technicians and engineers, much like IT folks today, were the keepers of what made it to air.

That all changed when the Sony Umatic VTR was discovered by news departments in the 70s. Now content trumped the holy grail of quality. Even though at the time sending a Umatic VTR to air often broke at least one technical rule still in the FCC regulations, the writing was on the wall. Multimedia content producers could now decide what platforms suit their business needs. Much of those were from generations of new users that had no concept of "broadcast quality."

While the K-Frame eventually made it to market, the off the shelf hardware part of the "Galaxy" quest did not. The problem was that Andreoli would not allow any of the drivers for OTS hardware, or the OS and other low level software to be modified. It was simply too early to adopt this standard off the shelf approach. It still wouldn't work at that time with real time HD video.

Under Andreoli Grass Valley outsourced its final assembly and testing operations from its Nevada City headquarters in July 2013, followed shortly by a lay-off of 34 local employees. After the outsourcing, the company's Nevada City facility continued to handle purchasing, customer support and switcher engineering. In 2009, Grass Valley still had nearly 300 employees at its Nevada City facility. Following another 10 percent reduction the following year, the company had around 270 employees in 2011 in Nevada City. After additional outsourcing it was below 200.

At the end of that year the increasingly wanderlust company moved its headquarters to Hillsboro, Oregon to an existing office inherited from Tek. soon Grass Valley moved up the road from its former Profile server digs in Beaverton.

While GV employment in the area was now dropping quite precipitously, the company had facilities in Burbank, Ca; Norcross, Ga.; Montvale, N.J.; Hillsboro, Ore.; Salt Lake City, Utah; and Miami; as well as Canada, along with several European countries, Dubai, Russia, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, and a handful of Asian countries. It was rapidly becoming a citizen of the world and becoming only loosely coupled to the land of its founding.

When Alain Andreoli stepped down in 2013. The writing was on the wall.

Tim Thorsteinson

Chuck Meyer was on a plane sitting next to David Golob during the time when Alain Andreoli was getting ready to step down. Golob at the time was chairman of GV's board. As you recall he was the Francisco partner instrumental in buying GV. As a joke Chuck suggested they hire Tim Thorsteinson. Thorsteinson was GV's President when Tek sold the company, and again when Gooding sold it.

Six months later Golob made the following announcement in January of 2013: "We are pleased to have Tim Thorsteinson join Grass Valley at this pivotal point in the company's transformation. Tim's in-depth industry knowledge and his proven track record of value creation will ensure Grass Valley's continued success as an independent leader in the rapidly evolving broadcast infrastructure market."

Besides moving up the Tek ranks and running GV before, then leaving in 2003 to become president of Leitch. Thorsteinson had also been President of the broadcast communications division of Harris Corp., and president when Harris Corp. acquired Leitch in 2005. He resigned from Harris in 2009.

"Grass Valley is uniquely positioned to help lead the broadcast industry into the multi-platform era and I am excited to be joining the team," Thorsteinson said. On another occasion he said, "I love Grass Valley, it's always been a great business and a solid brand.' But he also warned that 2013 would be a difficult year. He was there to sell and cash out the investment for Francisco Partners. True?

Mark Hilton, who was originally hired by Tek in Oregon, came down to GV in the late 90s, had left in 2005 as he did not like what was going on with Thomson, and went to work for HP for nine years. Thorsteinson had contacted him, and said that they were about to be sold, and he didn't know where or how they would use him but it was exciting times and so Hilton was interested. Hilton was the person who restarted the modular division after Fjeldstad had shut its R&D down in the 90s.

During the second half of 2013 there was a huge fall in sales in the broadcast industry. Companies in the industry saw declines of 10-40% sales. Part of that was the lull after the large extravaganza NBC had put on for the London Olympics. NBC broadcast all events live through either television or digital platforms. They provided 5,535 hours of coverage across NBC, NBC Sports Network, MSNBC, CNBC, Bravo, Telemundo, NBCOlympics.com, along with two specialty channels, and the first-ever 3-D platform. That surpassed the coverage of the 2008 Beijing Olympics by nearly 2,000 hours. NBC itself accounted for 272 hours of coverage. Internet and cloud infrastructure advancements, along with very large storage systems pushed the rush towards the cloud.

The Olympics often dictated the television equipment cycle. Two years before the Olympics NBC, who had been sole U.S. broadcaster of the Olympics since 1988, along with the rights holders in other countries around the world, would bulk up on the "latest and greatest" gear. Then afterward, budgets busted, and the propagation of much of that gear pushed outward to the networks other facilities and sold off to others, famine would strike. 2013 shaped up to be worse than normal. In addition Europe was still recovering from the 2008 economic crisis, especially Cyprus, Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain.

Increasingly, the "commoditization" of products was occurring, as standard platforms were able to do more processing, software was becoming the value added product. Grass Valley decided that soon it would begin selling software licenses for their products, which could become a nice revenue stream.

"We were No. 1 or 2 in switchers, routers, servers, news systems. I intend for us to be there again." Thorsteinson said at the time. All the while what Thorsteinson was really doing was positioning the company to be bought so Francisco Partners could cash out. That happened when a company that many at the time thought was in a position to brake the cyclic peddling of this venerable broadcast equipment vendor, stepped forward.

Soon GV was no longer in the Francisco Partners portfolio. Belden took over in February 2014 for around $200 million. Francisco Partners walked away with around $50 million in profits.

Being Bigger - Belden

Biologists note that bigger species are better at capturing prey, they can travel longer distances, and support bigger brains. Economy of scale is something biology has known for hundreds of millions of years. So why hasn't evolution made every species freaking huge? To quote Aaron Clauset of the Santa Fe Institute and Doug Erwin of the Museum of Natural History, "The tendency for evolution to create larger species is counterbalanced by the tendency of extinction to kill off larger species."

To quote Morgan Housel writing for the Collaborative Fund "Body size in biology is like leverage in investing: It accentuates the gains but amplifies the losses. It works well for a while and then backfires spectacularly at the point where the benefits are nice, but the losses are lethal."

Bugs can fall from heights thousands of times their own height with little to no damage. Small rodents maybe 50 times. A human is done it they fall from 10 times their height. An elephant: twice its height and it is history.

Big animals require more of everything: land, and food. Food is why the larger animals fail during a famine. They have other drawbacks; can't hide easily, move slow, reproduce slow. The biggest advantage is their best and worse: being at the top-of-the-food chain status means they usually don't need to adapt, but very bad when adapting is required. That is why the cockroach, and bacteria will be here long after we are gone, and why dinosaurs disappeared 65 million years ago.

Large companies that could not adapt: Sears, Kodak, Blockbusters, Polaroid, Toys R us, Pan Am, Borders, Tower Records, Radio Shack.

Blockbusters, Toys R Us, and Radio Shack failed because they ignored the Internet. Sears was actually an early explorer when it came to online sales. But it gained a reputation for not caring for its employees, which showed in its stores. Things got worse and human nature took over, no one wants to be associated with or do business with a failure. In the case of Pan Am the market environment changed and it didn't. Kodak and Polaroid, held on too long to technologies they pioneered and would not compete against.

As we know being first does not guarantee success. Just look to Myspace and Yahoo!. A failure that actually was very close to where the business is going today, was the squandering of $99 billion that happened when AOL and Time Warner merged. The timing was bad, right before the dot-com bubble burst. AOL shareholders owned 55 percent of the combined company while Time Warner shareholders owned 45 percent. AOL's co-founder, chairman and chief executive officer, Steve Case, became chairman of the new company, while Time Warner chairman and CEO Gerald Levin was named its CEO.

The behemoth, $350 billion at the time of the merger, mega-corporation was created at the beginning of 2000 when the two merged. AOL had an early online audience, and Time Warner had a television audience. In theory the company should have dominated in every type of media, including music, publishing, news, entertainment, cable, and the Internet. AOL's valuation was more valuable in market cap terms than many blue chips stocks.

Even though they merged officially, that never happened operationally. It appeared that no one did any due diligence as to whether the two cultures would mesh. The aggressive and, many said, egotistical and condescending AOL people appalled the more sedate and corporate Time Warner side. Cooperation and promised synergies failed to materialize as mutual disrespect came to dominate their relationships.

Two things led to the company's eventual demise. The dotcom bubble burst, and the economy went into a recession. Advertising dollars dried up. The second was technology. While AOL was the king of the dial-up Internet world, it was rapidly being supplanted by always-on, and much faster broadband. At the time of the merger, half the country had Internet access, but only 3% had broadband. AOL's business model was based on payment for a monthly dial up subscription. Starting in the 2000s a business Time Warner was already in, cable, was rapidly eating into the need for AOL's part of the business.

In 2002, AOL Time Warner reported a quarterly loss of $54 billion, the largest ever for a U.S. company. In the couple of years after the acquisition AOL's value fell by 90%. Time Warner spun off AOL in 2009 for pennies on the dollar. Levin,was widely blamed by shareholders for allowing Time Warner and its stable old-media assets to be effectively taken over and dragged down by the ailing new-media division, resigned in December 2001. In 2018, AT&T acquired Time Warner.

We just saw how Thomson thought economies of scale would make them more efficient. Economic evolution pushed them that direction, so they could bring more value to the stockholders. But when is too big? When does economies of scale become self-destructive? Thomson was well on its way to being the dominant force in it's industry. But it bought its size through leverage. When the economy was good, and stable, seemed like a great idea. When world wide valuations crashed starting in 2008, it became a house of cards. Many thought the Thomson saga was mainly due to bad luck or timing.

The kind of corporate culture that lets companies dominate an industry is not friendly to people who say, "I think we've grown too fast. Maybe we should scale back." They'll keep pushing until they're forced to make painful cuts.

They say that someone with a 110 IQ, but the ability to recognize when the world changes, will always beat the person with a 140 IQ and rigid beliefs. You can have a penthouse full of smart people running a company whose knowledge was acquired 20 or 30 years ago when the rules of the game were dramatically different. That acquired knowledge was gained at a cost of money, time, ward work, and humiliation. That is a sunk cost that you don't want to write off easily as people tend to cling to what they already know.

Marc Andreessen, co-author of the first widely used web browser, Mosaic, a co-founder of Netscape, and co-founder and general partner of Silicon Valley venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz, encourages the idea of "strong beliefs, weakly held." That is the ability to focus on an idea but having the humility to let it go when its proven wrong.

John Stroup

John Stroup found himself as the CEO at a fat lazy Midwest (St. Louis) industrial manufacturing company called Belden in 2005. Before joining Belden, he worked as a senior executive for a company called Danaher, and he was responsible for global business operations around the world. In the small world department, that is the company that bought Tek in 2007.

Stroup was able to increase the efficiency and profitability of the company. He managed to get Belden's share price up, but he could only go so far unless he found a way to greatly increase sales, and Belden had a significant share of the cable business already. The other option was to expand the company. Belden was sitting on a pile of cash, and Wall Street wanted him to do something with it. The standard rule of business is you invest in what's adjacent to you. Again size should yield synergy. The sales force should become more efficient with more products to offer, along with all the back office savings. You are selling more product to the same customers, and at the same time selling the same product to different customers.

So he started to expand Belden into the markets that they already served. He considered their markets as enterprise, industrial and broadcast. In the broadcast arena, they got excited about the idea of getting more involved in active components. And just like many broadcast vendors, Belden considered itself a high-mix, low-volume company, and a strong commitment to lean manufacturing, so almost everything they make was built to order.

Belden broke out of its wire and cable mold with the 2007 acquisition of Ethernet switch maker Hirshmann. It made industrial Ethernet switches used for automation. Two years later it bought a company much better known to broadcasters, Telecast. The company was a supplier of fiber conversion products for news gathering (ENG), and venue infrastructures. In 2011, it acquired ICM Corporation, a broadcast connectivity company, and the broadcast networking part of Thomas & Betts.

In July 2012 it made its first big acquisition as it started its run up to do what Thomson tried but failed doing. It brought Miranda, which began as a small Montreal-based broadcast technology provider in 1959, the same year that Grass Valley was founded. There was only a four month courtship before the deal was finalized. Compared to other companies in the business, Miranda had seen a fairly respectable increase in revenue, and was doing well in emerging markets in Asia. Strath Goodship, a former Miranda CEO, was brought back to lead Miranda. Belden kept the Miranda brand name. Miranda at the time was a $200 million a year in revenue company.

Denis Suggs, executive vice president for the Belden Americas Group, oversaw the acquisition. The acquisition made Belden a $2 billion business. It was founded in 1902 and had sold cable into the broadcast industry since 1932. As a cable alone business it was at $1.4 billion a year, of which $50 million in cable were sold to broadcasters. Suddenly in 2012 their broadcast business was almost $300 million.

As became a theme, Miranda was an important investment to the local teacher's union, and the Quebec providence, who looked upon Miranda as a job creation entity. Soon after Miranda bought NVISION in 2008, as we will see in chapter 17, they moved NVISION's PCB fab and manufacturing facilities to Montreal. So almost immediately Miranda convinced Belden to move Telecast's manufacturing, which was out of Worcester, MA, to Miranda's Quebec, manufacturing facilities. Telecast's products also became a product line within the Miranda portfolio. Telecast Worcester office remained open for sales and service calls, sharing space with Belden's recently acquired Mohawk Cable business.

Goodship said there is "surprisingly little overlap" in products between the two companies. In fact, Miranda had attempted to produce fiber conversion products several years before "and failed," according to Goodship. Telecast also had a loyal following among the mobile truck community.

Belden did well with the Miranda acquisition, as by the beginning of 2014 Belden stock had doubled.

GV's Turn

In March of 2014 it finally became GV's turn. Belden bought GV from Francisco Partners and immediately merged it with Miranda. Marco Lopez was the president of Miranda at the time, and he became the President of the combined GV/Miranda company. Interestingly the GV brand was kept, and the Miranda brand retired. But in tribute to the part of the company that actually controlled the company but lost its own name to a small town in California, Miranda's magenta color scheme replaced Grass Valley's green theme.

Was that the plan all along? Did Belden initiate it, or did Miranda? Did GV know what was going to happen? Was this something Thorsteinson had a hand in? Golob?

With the acquisition of Grass Valley, the percentage of revenue from cable products for Belden was about 35 percent. When Stroup joined the company in 2005, it was almost the entire company. By 2015 Belden was a $2.4 billion company. Broadcast accounted for about $1 billion of the company's revenue.

Miranda and Grass Valley had some overlap, but each had products, and strengths the other didn't have. Belden's video business went from $200 million to $500 million. At the time Stroup was still talking about economies of scale.

The Miranda product line was heavier in routing (thanks to NVISION), playout, multiviewers, monitors, graphics, and branding, while Grass Valley focused more on production switchers, automation and editing, servers, cameras, and camera systems. In theory this broad product offering makes things easier for their customers. Smaller vendors would have to pursue a best-of-breed route, selling niche products. Customers going this route are vulnerable to one piece of their puzzle failing, either by a financial issue with the vendor, or simply a technology snafu. The fact that Belden was financially stable and the additional support of Miranda, made many customers, especially the mobile production truck vendors who were heavily committed to GV, feel better.

While Belden had St. Louis as their headquarters, it was a small office, of about 40 financial people, the legal team, and the human resources staff. Their manufacturing was all over the world; United States, Canada, Mexico, China, Brazil, Germany, Czech Republic, United Kingdom, France, Netherlands. They tended to build products pretty close to consumption. So Belden was quite comfortable with managing a global enterprise.

The headquarters of the combined companies ended up in Montreal. There was no chance at that point that Grass Valley would ever see the corporate HQ located in the area ever again. Francisco Partners originally ran GV from San Francisco and then moved it to Oregon. While GV was the larger of the two companies (correct?), it was already scattered around the globe, with only a small percentage still in the Grass Valley area. In addition Belden had a facility near Miranda's and thus they were familiar with Miranda's operation. Quebec also had big tax incentives to be there. By the time Grass Valley was merged with Miranda, Grass Valley had no manufacturing left in the Grass Valley area.

(Who was Straph, was he on his way out At the time of the merger? A quote from someone "He was a guy who loved to watch his first knights fight.")

Some GV employees were moved. Mark Hilton moved to Montreal for a year for the modular products, now being built there. He moved back to Grass Valley, as one of the dwindling number of employees there, and in 2017 he then took over as VP of the Live Group. This included cameras, switchers, and replay. Cameras are built in Bretta, Netherlands, and replay was based on the K2, which was developed up in Oregon, and evolved out of the Profile. As Grass Valley continued to downsize in their namesake area, Mark was left go in 2019.

Buying up the U.K.

But Belden still was not done. In February of 2018 Snell & Wilcox was acquired. (By Belden or GV?)

The Newbury, U.K. company had been founded by Roderick Snell, in 1973. It had re-branded as Snell Advanced Media or SAM. Many of its product lines overlapped with GV's. But somethings Snell was deemed to do better. With the acquisition of SAM the focus moved from the K2 replay system headquartered in Beaverton to theirs.

SAM was an outgrowth of a 2009 merger of Snell & Wilcox and Pro-Bel, another U.K. company. The resulting company took the name Snell. Pro-Bel developed automation, media management and master control technology as well as routing, control and signal modular products. Snell & Wilcox developed systems for video playout, mastering, repurposing, live production switching, and it also did signal modular products.

In March 2014 it was announced that Snell had been acquired by Quantel and the combined company took the name SAM. Quantel made its name in the graphics arena. Introduced in 1981 the Quantel Paintbox was a dedicated computer graphics workstation for composition of broadcast television video and graphics. Its design emphasized the studio workflow efficiency required for live news production. It had a price of about $250,000 per unit (equivalent to $374,000 in 2020). Launched nine years before the release of Adobe Photoshop there was nothing else to touch it performance wise at the time. What the Paintbox offered would have been impossible without expensive, cumbersome, and dedicated hardware. The Paintbox was still going strong into the 1990s.

Ahead of its time in capability Quantel's entry into the DVE market in 1982 was the Mirage. It could warp a live video stream by texture mapping it onto a three-dimensional shape. Not possible until then. In 1985 Quantel introduced the first of their series of "H" non-linear editors, Harry, followed by Harriet in 1990, and Henry in 1992. Quantel products were always proudly situated at the very high end. The cost of spending a couple hours in a Henry editing suite in the 90s would buy you a computer fully loaded with software today that would deliver the same results.

Quantel reached their peak with the Pablo, a color correcting tool which James Cameron used to post produce the 3D Avatar movie in 2009. The Pablo was followed by the Pablo Rio, a complete color correcting and finishing system.

Despite becoming the industry standard for TV graphics and post production, with hundreds sold around the world, the company began to stagger from 2005 onwards. So in 2014 it acquired SAM. SAM was another British high-end hardware-based manufacturer, famous for their Alchemist standards converter. SAM also had a loyal following with their own line of high-end production switchers.

After the departure of Quantel's CEO Ray Cross, Tim Thorsteinson was appointed CEO in February 2015, until June 2017 when it was announced that Tim Thorsteinson was stepping down as CEO and being replaced with Eric Cooney.

(Why did Thorsteinson step down? Was it because of cancer? From past history he should have sold SAM to GV. What a convoluted tale that would be. How many people can sell a company more than once (Besides Birney, and maybe Dan) and then sell another to the company he sold?)

In January 2018 Tim Shoulders became GV president, and subsequently moved to Montreal. He has a Bachelor of Arts in Finance and Accounting from Ball State University and joined Belden in 2011. He led Belden's global Broadcast AV Cable business as vice president/general manager and then served in the same role for the global Industrial Cable business. He was known in the company as merger and acquisition specialist. (Was he promoted to look into selling GV?)

With SAM now incorporated into the "Group," Grass Valley continued to be headquartered in Montreal. Eric Cooney, former president, and CEO of SAM stayed on in an advisory role. The SAM brand was retired but many of its products are still offered under the GV brand.

Everywhere but here

By June 2015 what was left of the company in the Grass Valley area was consolidated into what was originally the NVISION building after completion of a $3 million renovation of the building. It was redesigned to house 200 people. The company moved out of the Providence Mine site, and effectively moved back to its namesake town, and out of Nevada City. It had not been since the early 60s that the Grass Valley Company was actually in Grass Valley proper. Now it was, but it would turn out not to last.

At the time the area was happy and proud that the world-renowned company would stay in the area. Some in the area liked to think of Nevada County as "Video Valley" due to the technology cluster of other video companies. "I think it's very nice to have Grass Valley back in Grass Valley," said Grass Valley Mayor at the time Jason Fouyer in a cheerful ribbon-cutting ceremony before about 150 workers, contractors, city and county officials and residents. "They have the entire world they could have moved to, and they chose to keep it here." A bit glib seeing that the company's building was a mere outpost of the company at that point. And the signs were still bad and growing worse. The Providence mine site at its height had 400 based there. Now there were about 120 in the former NVISION building.

About that time the company decided to combine engineering and strategic marketing groups into product units. The term divisions were dropped. There were four:

1) Live Production

Cameras – development and manufacturing in Bergschot, Breda, Netherlands

Switchers – development only in Grass Valley, manufacturing in Montreal

Replay – development and manufacturing in Hillsboro, OR, and Newbury, Berkshire, United Kingdom

2) News Production

Editing and Transcoding – development, and manufacturing in Kobe Japan

Video Production and Content Management – development and manufacturing in Hillsboro,OR, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, and Weiterstadt, Germany

Automated Productions – development and manufacturing in Hillsboro, OR, Montreal, Quebec, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Servers, Storage, & Recorders – development and manufacturing Hillsboro, OR, Kobe Japan, Newbury, Berkshire, United Kingdom

3) Playout

Integrated Playout – development and manufacturing in Castle Donington, Derbyshire, United Kingdom, Newbury, Berkshire, United Kingdom

Master Control & Branding – development and manufacturing in Montreal, Quebec, Newbury, Berkshire, United Kingdom

Transmission servers & Storage – development and manufacturing, Hillsboro, OR, Newbury, Berkshire, United Kingdom

4) Networking

Signal Processing – development and manufacturing, Montreal, Quebec

Multiviewers – Montreal, Quebec, Newbury, Berkshire, United Kingdom

Routers – development only in Grass Valley, development and manufacturing, Montreal, Quebec, Newbury, Berkshire, United Kingdom

Monitoring & Control – development and manufacturing, Montreal, Quebec; Newbury, Berkshire, United Kingdom

Fiber Transport – development and manufacturing, Bergschot, Breda, Netherlands

Notice that Grass Valley only shows up twice. No manufacturing, only engineering support and development.

(Was the fact that any of the company still exists in the area mainly due to the optics of having no presence here?)

Almost all of the other major acquisitions along the way are still represented from an engineering and development standpoint.

Quantel-SAM acquisition is well represented in Newberry:

Replay, Servers, Storage, & Recorders, Integrated Playout, Master Control & Branding, Transmission servers & Storage, Multiviewers, Routers, Monitoring & Control

Also from Quantel-SAM , Castle Donington, Derbyshire, United Kingdom

Integrated Playout

The piece that Tek left behind in Hillsboro:

Replay, Video Production and Content Management, Automated Productions, Servers, Storage, & Recorders, Transmission servers & Storage

The Miranda part of the deal in Montreal: